086

Daniel Barber

Climate Histories

Today ‘s conversation is with Daniel Barber about his book ‘Modern Architecture and Climate Design before Air Conditioning’.

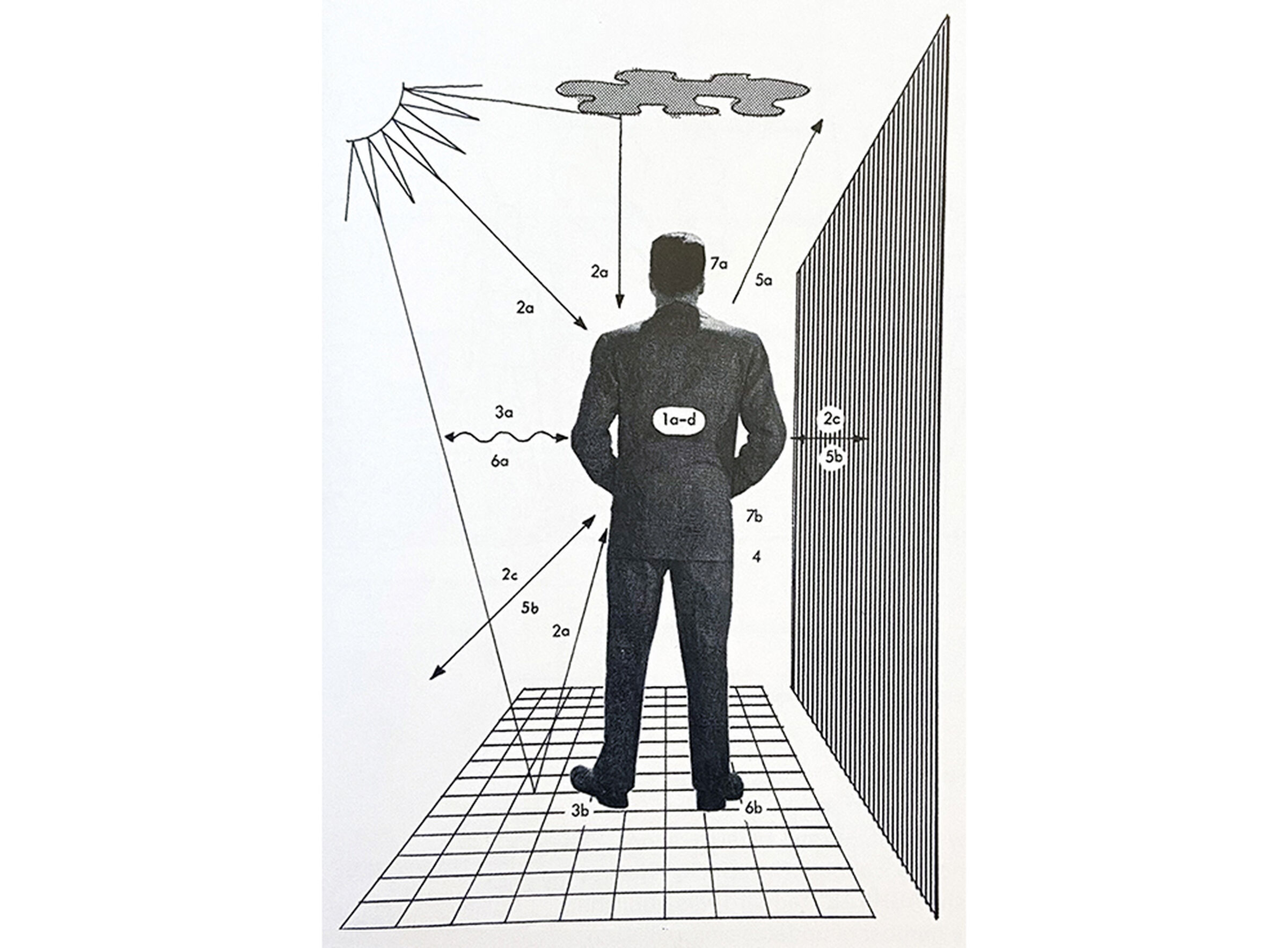

Victor Olgyay, ‘Heat exchange between Man and His Surroundings,’ from Design with Climate, 1963

What does it mean to ‘reframe the past in the service of the future’. This is a central question asked by my guest today.

Understanding the cultural context of a period of time helps reorient our assumptions of not only WHY decisions were made but how we carry that knowledge into the future. ‘How we tell stories informs the stories we tell’, to paraphrase Donna Haraway.

This is probably most clearly represented with climate. It’s easy to forget that knowledge largely accepted today in popular literature and professional journals has not been around all that long. The term Anthropocene is only 20 years old, made popular by biologist Eugene Stormer and chemist Paul Crutzen. We can look back to the mid 19th century to Eunice Newton Foote’s studies that gases in the atmosphere can increase the temperatures of our planet, but it wouldn’t be until the 1950’s when scientists formed a greater consensus of these facts. Even less time since people accepted this as common knowledge that could be used to inform our daily choices.

Even the idea that fossil fuels might be a finite resource has not always been a concern for even the most coal and oil centric corporations. But the origins of mechanical systems in our buildings for dehumidify the air in textile factories, and comfort for our commercial spaces predates nearly all of these discussions.

Climate has had a less than flattering seat in the architect’s design education, even to this day. I think this is in part because the architect’s education relies so heavily on case studies and technological histories that stand somehow as static monuments to be referenced formal techniques applied in their own work. To inhabit the sociological timelines, to question what was known by whom when such formal and technological techniques were deployed (as audacious or reserved as they might be) is an altogether different set of muscles.

I’m not walking through this borderline irresponsible history lesson to deflect responsibility but history is not monolithic. It’s splintered and lived unevenly by many people. Many histories can be said to exist and even more futures are viable for forming.

Climate is a culturally formed concept. As political battles continue today in response to climate change, the media often positions this subject as an objective truth, scientific truths. And of course, aspects of climate discourse require scientific knowledge but there are aspects of cultural subjectivity; like what is determined to be ‘comfortable’. There is no global consensus of what temperature and humidity level is considered comfortable in an interior space. What about levels of discomfort that people are willing to put up with within their homes for a portion of a day or season, how willing are people to shift routine to meet their climatic comfort. To think about how climate has been portrayed in popular culture and literature of the last century is eye opening. How much more frequently does a teenager even hear that term ‘climate’ compared to what we might have as a kid.

There is no singular notion of climate (personal comfort controls, environmental preservation, energy resources, social inequality, species extinction and evolving lifestyle) to name a few. Architecture and design of course touch on each of those desperate yet intertwined topics. Should architecture be discussed any more as finished object best photographed on the day of completion or more like landscapes that will evolve over time and requires continuous maintenance.

It’s probably best for each of us to acknowledge that as design professionals (or even just as humans) we can’t possibly imagine the repercussions and opportunities for how we will define and judge success in the next 100 years.

As my guest Daniel Barber suggests within his book ‘Modern Architecture and Climate Design before Air Conditioning’ that we don’t even fully understand the settings of the past 100 years that we rely on for guidance today. I don’t mention this to point out how naive we would be to pretend to know what lies ahead, but instead to more opportunistically say, that this discourse hasn’t been written yet. We don’t write or build to just state facts and claim status for what we assume to be original ideas, we do so to inform future discourse. Or as Daniel Barber says in his book ‘to reframe the past in the service of the future’.

Thanks to Richard Devine for Sample permissions.

Daniel Barber

Daniel A. Barber is Associate Professor and Chair of the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. His research and teaching narrate eco-critical histories of architecture and seek pathways into the post-hydrocarbon future. We discuss on this episode his most recent book ‘Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning (Princeton UP, 2020)